in the term osteomyelitis, what does the root refer to?

| Osteomyelitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bone infection |

| |

| Osteomyelitis of the 1st toe | |

| Specialty | Communicable diseases, orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Pain in a specific bone, overlying redness, fever, weakness[ane] |

| Complications | Amputation[two] |

| Usual onset | Immature or old[i] |

| Duration | Short or long term[two] |

| Causes | Bacterial, fungal[2] |

| Take a chance factors | Diabetes, intravenous drug use, prior removal of the spleen, trauma to the area[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Claret tests, medical imaging, bone biopsy[ii] |

| Differential diagnosis | Charcot's joint, rheumatoid arthritis, infectious arthritis, behemothic prison cell tumor, cellulitis[1] [three] |

| Handling | Antimicrobials, surgery[4] |

| Prognosis | Low risk of death with treatment[5] |

| Frequency | ii.four per 100,000 per year[half dozen] |

Osteomyelitis (OM) is an infection of os.[i] Symptoms may include hurting in a specific os with overlying redness, fever, and weakness.[1] The long bones of the artillery and legs are most commonly involved in children e.g. the femur and humerus,[7] while the feet, spine, and hips are most ordinarily involved in adults.[2]

The cause is usually a bacterial infection,[1] [7] [ii] but rarely can be a fungal infection.[8] Information technology may occur by spread from the blood or from surrounding tissue.[4] Risks for developing osteomyelitis include diabetes, intravenous drug use, prior removal of the spleen, and trauma to the area.[ane] Diagnosis is typically suspected based on symptoms and basic laboratory tests as C-reactive protein (CRP) and Erythrocyte sedimentation charge per unit (ESR).This is because plain radiographs are unremarkable in the first few days post-obit astute infection.[7] [2] Diagnosis is further confirmed by claret tests, medical imaging, or bone biopsy.[two]

Treatment of bacterial osteomyelitis often involves both antimicrobials and surgery.[7] [iv] In people with poor blood flow, amputation may be required.[2] Handling of the relatively rare fungal osteomyelitis as mycetoma infections entails the utilise of antifungal medications.[9] In contrast to bacterial osteomyelitis, amputation or big bony resections is more mutual in neglected fungal osteomyelitis, namely mycetoma, where infections of the human foot account for the majority of cases.[8] [9] Treatment outcomes of bacterial osteomyelitis are mostly expert when the condition has just been present a short fourth dimension.[vii] [ii] Almost 2.4 per 100,000 people are affected each yr.[6] The young and old are more commonly affected.[seven] [1] Males are more commonly afflicted than females.[3] The condition was described at to the lowest degree as early on as the 300s BC by Hippocrates.[4] Prior to the availability of antibiotics, the chance of death was significant.[10]

Signs and symptoms [edit]

Symptoms may include pain in a specific bone with overlying redness, fever, and weakness and inability to walk especially in children with acute bacterial osteomyelitis.[7] [1] Onset may be sudden or gradual.[1] Enlarged lymph nodes may be present.[11] In fungal osteomyelitis, there is usually a history of walking bare-footed, particularly in rural and farming areas. Opposite to the mode of infection in bacterial osteomyelitis, which is primarily blood-borne, fungal osteomyelitis starts as a pare infection, then invades deeper tissues until information technology reaches os.[8]

Cause [edit]

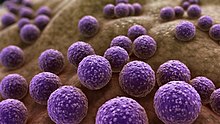

Drawing of Staphylococcus bacteria

| Age grouping | Most common organisms |

|---|---|

| Newborns (younger than 4 mo) | Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacter species, and group A and B Streptococcus species |

| Children (aged 4 mo to four y) | Southward. aureus, grouping A Streptococcus species, Haemophilus influenzae, and Enterobacter species |

| Children, adolescents (anile 4 y to adult) | S. aureus (lxxx%), grouping A Streptococcus species, H. influenzae, and Enterobacter species |

| Adult | Due south. aureus and occasionally Enterobacter or Streptococcus species |

| Sickle cell anemia patients | Salmonella species are most common in patients with sickle jail cell affliction.[12] |

In children, the metaphyses, the ends of long bones, are usually affected. In adults, the vertebrae and the pelvis are most commonly affected.[7]

Astute osteomyelitis near invariably occurs in children who are otherwise good for you, because of rich claret supply to the growing bones. When adults are affected, it may be because of compromised host resistance due to debilitation, intravenous drug corruption, infectious root-canaled teeth, or other disease or drugs (e.g., immunosuppressive therapy).[7]

Osteomyelitis is a secondary complication in 1–three% of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis.[13] In this case, the bacteria, in general, spread to the os through the circulatory system, first infecting the synovium (due to its college oxygen concentration) before spreading to the adjacent bone.[thirteen] In tubercular osteomyelitis, the long bones and vertebrae are the ones that tend to be affected.[xiii]

Staphylococcus aureus is the organism about commonly isolated from all forms of osteomyelitis.[13]

Bloodstream-sourced osteomyelitis is seen nigh frequently in children, and nearly 90% of cases are caused by Staphylococcus aureus. In infants, S. aureus, Group B streptococci (most common[14]) and Escherichia coli are ordinarily isolated; in children from one to 16 years of age, S. aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Haemophilus influenzae are common. In some subpopulations, including intravenous drug users and splenectomized patients, Gram-negative bacteria, including enteric leaner, are pregnant pathogens.[15]

The most common form of the disease in adults is caused by injury exposing the bone to local infection. Staphylococcus aureus is the most mutual organism seen in osteomyelitis, seeded from areas of contiguous infection. But anaerobes and Gram-negative organisms, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Due east. coli, and Serratia marcescens, are besides common. Mixed infections are the rule rather than the exception.[15]

Systemic mycotic infections may as well cause osteomyelitis. The two virtually common are Blastomyces dermatitidis and Coccidioides immitis.[ citation needed ]

In osteomyelitis involving the vertebral bodies, about one-half the cases are due to S. aureus, and the other half are due to tuberculosis (spread hematogenously from the lungs). Tubercular osteomyelitis of the spine was so common before the initiation of effective antitubercular therapy, information technology acquired a special name, Pott's disease.[ commendation needed ]

The Burkholderia cepacia circuitous has been implicated in vertebral osteomyelitis in intravenous drug users.[16]

Pathogenesis [edit]

In general, microorganisms may infect bone through ane or more of three basic methods

- Via the bloodstream (haematogeneously) – the nigh common method[17]

- From nearby areas of infection (every bit in cellulitis), or

- Penetrating trauma, including iatrogenic causes such as joint replacements or internal fixation of fractures or secondary periapical periodontitis in teeth.[13]

The area normally affected when the infection is contracted through the bloodstream is the metaphysis of the os.[17] Once the bone is infected, leukocytes enter the infected surface area, and, in their endeavor to engulf the infectious organisms, release enzymes that lyse the bone. Pus spreads into the os's blood vessels, impairing their menstruum, and areas of devitalized infected bone, known as sequestra, form the basis of a chronic infection.[thirteen] Often, the body will effort to create new bone around the area of necrosis. The resulting new os is often called an involucrum.[xiii] On histologic examination, these areas of necrotic bone are the basis for distinguishing between astute osteomyelitis and chronic osteomyelitis. Osteomyelitis is an infective process that encompasses all of the bone (osseous) components, including the bone marrow. When information technology is chronic, it can lead to bone sclerosis and deformity.[ citation needed ]

Chronic osteomyelitis may be due to the presence of intracellular leaner.[xviii] Once intracellular, the bacteria are able to spread to adjacent bone cells.[19] At this signal, the bacteria may be resistant to sure antibiotics.[twenty] These combined factors may explain the chronicity and difficult eradication of this affliction, resulting in significant costs and disability, potentially leading to amputation. The presence of intracellular bacteria in chronic osteomyelitis is likely an unrecognized contributing gene in its persistence.[ citation needed ]

In infants, the infection can spread to a joint and cause arthritis. In children, large subperiosteal abscesses can class because the periosteum is loosely attached to the surface of the bone.[13]

Because of the particulars of their blood supply, the tibia, femur, humerus, vertebrae, maxilla and the mandibular bodies are especially susceptible to osteomyelitis.[21] Abscesses of any bone, however, may be precipitated by trauma to the affected area. Many infections are caused by Staphylococcus aureus, a member of the normal flora found on the pare and mucous membranes. In patients with sickle cell disease, the nearly common causative agent is Salmonella, with a relative incidence more than twice that of S. aureus.[12]

Diagnosis [edit]

Mycobacterium doricum osteomyelitis and soft tissue infection. Computed tomography scan of the correct lower extremity of a 21-year-quondam patient, showing abscess formation adjacent to nonunion of a correct femur fracture.

Extensive osteomyelitis of the forefoot

Osteomyelitis in both feet equally seen on bone scan

The diagnosis of osteomyelitis is complex and relies on a combination of clinical suspicion and indirect laboratory markers such as a loftier white claret cell count and fever, although confirmation of clinical and laboratory suspicion with imaging is unremarkably necessary.[22]

Radiographs and CT are the initial method of diagnosis, only are not sensitive and only moderately specific for the diagnosis. They can bear witness the cortical destruction of advanced osteomyelitis, but can miss nascent or indolent diagnoses.[22]

Confirmation is almost often past MRI. The presence of edema, diagnosed as increased signal on T2 sequences, is sensitive, but not specific, as edema can occur in reaction to side by side cellulitis. Confirmation of bony marrow and cortical devastation by viewing the T1 sequences significantly increases specificity. The administration of intravenous gadolinium-based contrast enhances specificity further. In certain situations, such as astringent Charcot arthropathy, diagnosis with MRI is still hard.[22] Similarly, information technology is limited in distinguishing avascular necrosis from osteomyelitis in sickle cell anemia.[23]

Nuclear medicine scans can exist a helpful adjunct to MRI in patients who have metallic hardware that limits or prevents effective magnetic resonance. Generally a triple phase technetium 99 based scan will show increased uptake on all three phases. Gallium scans are 100% sensitive for osteomyelitis but not specific, and may be helpful in patients with metallic prostheses. Combined WBC imaging with marrow studies has 90% accuracy in diagnosing osteomyelitis.[24]

Diagnosis of osteomyelitis is oftentimes based on radiologic results showing a lytic middle with a ring of sclerosis.[13] Culture of fabric taken from a bone biopsy is needed to identify the specific pathogen;[25] culling sampling methods such as needle puncture or surface swabs are easier to perform, merely cannot be trusted to produce reliable results.[26] [27]

Factors that may commonly complicate osteomyelitis are fractures of the bone, amyloidosis, endocarditis, or sepsis.[13]

Classification [edit]

The definition of OM is wide, and encompasses a wide variety of conditions. Traditionally, the length of time the infection has been present and whether there is suppuration (pus formation) or osteosclerosis (pathological increased density of bone) are used to arbitrarily classify OM. Chronic OM is frequently divers every bit OM that has been present for more than than one month. In reality, there are no distinct subtypes; instead, there is a spectrum of pathologic features that reflects a balance betwixt the type and severity of the cause of the inflammation, the immune system and local and systemic predisposing factors.[ citation needed ]

- Suppurative osteomyelitis

- Acute suppurative osteomyelitis

- Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis

- Chief (no preceding phase)

- Secondary (follows an astute phase)

- Non-suppurative osteomyelitis

- Diffuse sclerosing

- Focal sclerosing (condensing osteitis)

- Proliferative periostitis (periostitis ossificans, Garré's sclerosing osteomyelitis)

- Osteoradionecrosis

OM can also be typed according to the area of the skeleton in which it is nowadays. For case, osteomyelitis of the jaws is different in several respects from osteomyelitis nowadays in a long bone. Vertebral osteomyelitis is another possible presentation.[ citation needed ]

Handling [edit]

Osteomyelitis often requires prolonged antibody therapy for weeks or months. A PICC line or central venous catheter can be placed for long-term intravenous medication administration. Some studies of children with astute osteomyelitis report that antibody past mouth may exist justified due to PICC-related complications.[28] [29] It may require surgical debridement in severe cases, or even amputation. Antibiotics by mouth and past intravenous appear similar.[30] [31]

Due to insufficient testify it is unclear what the all-time antibiotic treatment is for osteomyelitis in people with sickle jail cell disease as of 2019.[32]

Initial offset-line antibiotic pick is determined past the patient's history and regional differences in common infective organisms. A treatment lasting 42 days is practiced in a number of facilities.[33] Local and sustained availability of drugs take proven to be more than effective in achieving prophylactic and therapeutic outcomes.[34] Open surgery is needed for chronic osteomyelitis, whereby the involucrum is opened and the sequestrum is removed or sometimes saucerization[35] can be done. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been shown to be a useful adjunct to the treatment of refractory osteomyelitis.[36] [37]

Before the widespread availability and use of antibiotics, blow fly larvae were sometimes deliberately introduced to the wounds to feed on the infected material, effectively scouring them clean.[38] [39]

At that place is tentative evidence that bioactive glass may besides be useful in long bone infections.[40] Support from randomized controlled trials, however, was non available as of 2015.[41]

Hemicorporectomy is performed in severe cases of Terminal Osteomyelitis in the Pelvis if further handling won't stop the infection. [42]

History [edit]

The word is from Greek words ὀστέον osteon, meaning bone, μυελό- myelo- meaning marrow, and -ῖτις -itis meaning inflammation. In 1875, American artist Thomas Eakins depicted a surgical procedure for osteomyelitis at Jefferson Medical Higher, in an oil painting titled The Gross Clinic.[ commendation needed ]

Fossil record [edit]

Evidence for osteomyelitis plant in the fossil record is studied by paleopathologists, specialists in ancient disease and injury. It has been reported in fossils of the big carnivorous dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis.[43] Osteomyelitis has been as well associated with the first testify of parasites in dinosaur basic.[44]

Come across besides [edit]

- Brodie abscess

- Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis

- SAPHO syndrome

- Garre's sclerosing osteomyelitis

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j k "Osteomyelitis". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2005. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved twenty July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Osteomyelitis". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). 2016. Archived from the original on nine Feb 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ a b Ferri, Fred F. (2017). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Wellness Sciences. p. 924. ISBN978-0323529570. Archived from the original on 2017-09-x.

- ^ a b c d Schmitt, SK (June 2017). "Osteomyelitis". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 31 (two): 325–38. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2017.01.010. PMID 28483044.

- ^ Bennett, John E.; Dolin, Raphael; Blaser, Martin J. (2014). Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 2267. ISBN978-1455748013. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- ^ a b Hochberg, Marc C.; Silman, Alan J.; Smolen, Josef Due south.; Weinblatt, Michael E.; Weisman, Michael H. (2014). Rheumatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 885. ISBN978-0702063039. Archived from the original on 2017-09-ten.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i El-Sobky, T; Mahmoud, S (July 2021). "Acute osteoarticular infections in children are oftentimes forgotten multidiscipline emergencies: across the technical skills". EFORT Open Reviews. 6 (seven): 584–592. doi:10.1302/2058-5241.6.200155. PMC8335954. PMID 34377550.

- ^ a b c El-Sobky, TA; Haleem, JF; Samir, Southward (2015). "Eumycetoma Osteomyelitis of the Calcaneus in a Kid: A Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation following Total Calcanectomy". Case Reports in Pathology. 2015: 129020. doi:ten.1155/2015/129020. PMC4592886. PMID 26483983.

- ^ a b van de Sande, Wendy; Fahal, Ahmed; Ahmed, Sarah Abdalla; Serrano, Julian Alberto; Bonifaz, Alexandro; Zijlstra, Ed (10 March 2018). "Endmost the mycetoma cognition gap". Medical Mycology. 56 (suppl_1): S153–S164. doi:10.1093/mmy/myx061. PMID 28992217.

- ^ Brackenridge, R. D. C.; Croxson, Richard Due south.; Mackenzie, Ross (2016). Medical Selection of Life Risks 5th Edition Swiss Re branded. Springer. p. 912. ISBN978-1349566327. Archived from the original on 2017-09-ten.

- ^ Root, Richard K.; Waldvogel, Francis; Corey, Lawrence; Stamm, Walter Due east. (1999). Clinical Infectious Diseases: A Practical Arroyo. Oxford University Printing. p. 577. ISBN978-0-19-508103-nine.

- ^ a b Burnett, G.Due west.; J.W. Bass; B.A. Cook (1998-02-01). "Etiology of osteomyelitis complicating sickle cell affliction". Pediatrics. 101 (2): 296–97. doi:10.1542/peds.101.2.296. PMID 9445507.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul G.; Fausto, Nelson; & Mitchell, Richard Northward. (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (eighth ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 810–11 ISBN 978-ane-4160-2973-1

- ^ Haggerty, Maureen (2002). "Streptococcal Infections". Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. The Gale Group. Archived from the original on 2008-03-25. Retrieved 2008-03-14 .

- ^ a b Carek, P.J.; L.M. Dickerson; J.Fifty. Sack (2001-06-fifteen). "Diagnosis and direction of osteomyelitis". Am Fam Medico. 63 (12): 2413–20. PMID 11430456.

- ^ Weinstein, Lenny; Knowlton, Christin A.; Smith, Miriam A. (2007-12-16). "Cervical osteomyelitis caused by Burkholderia cepacia after rhinoplasty". Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2 (1): 76–77. doi:ten.3855/jidc.327. ISSN 1972-2680. PMID 19736393.

- ^ a b Luqmani, Raashid; Robb, James; Daniel, Porter; Benjamin, Joseph (2013). Orthopaedics, Trauma and Rheumatology (second ed.). Mosby. p. 96. ISBN978-0723436805.

- ^ Ellington. "Microbial Pathogenesis" (1999).[ page needed ]

- ^ Ellington Journal of Os and Articulation Surgery (2003).[ folio needed ]

- ^ Ellington. Periodical of Orthopedic Inquiry (2006).[ page needed ]

- ^ King Physician, Randall W, Johnson D (2006-07-thirteen). "Osteomyelitis". eMedicine. WebMD. Archived from the original on 2007-11-09. Retrieved 2007-11-eleven .

- ^ a b c Howe, B. Yard.; Wenger, D. E.; Mandrekar, J; Collins, M. S. (2013). "T1-weighted MRI imaging features of pathologically proven not-pedal osteomyelitis". Academic Radiology. 20 (1): 108–14. doi:ten.1016/j.acra.2012.07.015. PMID 22981480.

- ^ Delgado, J; Bedoya, M. A.; Green, A. M.; Jaramillo, D; Ho-Fung, 5 (2015). "Utility of unenhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted MRI in children with sickle prison cell disease – can it differentiate bone infarcts from acute osteomyelitis?". Pediatric Radiology. 45 (13): 1981–87. doi:x.1007/s00247-015-3423-8. PMID 26209118. S2CID 7362493.

- ^

- ^ Zuluaga AF; Galvis W; Saldarriaga JG; Agudelo M; Salazar BE; Vesga O (2006-01-09). "Etiologic diagnosis of chronic osteomyelitis: A prospective study". Archives of Internal Medicine. 166 (1): 95–100. doi:ten.1001/archinte.166.1.95. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 16401816.

- ^ Zuluaga, Andrés F; Galvis, Wilson; Jaimes, Fabián; Vesga, Omar (2002-05-sixteen). "Lack of microbiological concordance between bone and not-bone specimens in chronic osteomyelitis: An observational study". BMC Infectious Diseases. 2 (i): 8. doi:ten.1186/1471-2334-2-8. PMC115844. PMID 12015818.

- ^ Senneville East, Morant H, Descamps D, et al. (2009). "Needle puncture and transcutaneous bone biopsy cultures are inconsistent in patients with diabetes and suspected osteomyelitis of the pes". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (7): 888–93. doi:10.1086/597263. PMID 19228109.

- ^ Keren, Ron; Shah, Samir Southward.; Srivastava, Rajendu; Rangel, Shawn; Bendel-Stenzel, Michael; Harik, Nada; Hartley, John; Lopez, Michelle; Seguias, Luis (2015-02-01). "Comparative Effectiveness of Intravenous vs Oral Antibiotics for Postdischarge Treatment of Astute Osteomyelitis in Children". JAMA Pediatrics. 169 (2): 120–28. doi:ten.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2822. ISSN 2168-6203. PMID 25506733.

- ^ Norris, Anne H; Shrestha, Nabin Thou; Allison, Genève M; Keller, Sara C; Bhavan, Kavita P; Zurlo, John J; Hersh, Adam L; Gorski, Lisa A; Bosso, John A (2019-01-01). "2018 Infectious Diseases Social club of America Clinical Do Guideline for the Direction of Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapya". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 68 (1): e1–e35. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy745. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 30423035.

- ^ Sæterdal, I; Akselsen, PE; Berild, D; Harboe, I; Odgaard-Jensen, J; Reinertsen, Eastward; Vist, GE; Klemp, Thou (2010). "Antibody Therapy in Hospital, Oral Versus Intravenous Treatment". Oslo, Kingdom of norway: Knowledge Heart for the Health Services at The Norwegian Found of Public Health. PMID 29319957.

- ^ Stengel, D; Bauwens, G; Sehouli, J; Ekkernkamp, A; Porzsolt, F (October 2001). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of antibody therapy for bone and joint infections". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 1 (3): 175–88. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00094-nine. PMID 11871494.

- ^ Martí-Carvajal, AJ; Agreda-Pérez, LH (7 October 2019). "Antibiotics for treating osteomyelitis in people with sickle cell affliction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (four): CD007175. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007175.pub5. PMC6778815. PMID 31588556.

- ^ Putland M.D, Michael S., Hyperbaric Medicine, Capital Regional Medical Eye, Tallahassee, Florida, personal inquiry June 2008.

- ^ Soundrapandian, C; Datta S; Sa B (2007). "Drug-eluting implants for osteomyelitis". Disquisitional Reviews in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems. 24 (6): 493–545. doi:10.1615/CritRevTherDrugCarrierSyst.v24.i6.10. PMID 18298388.

- ^ "Saucerization".

- ^ Mader JT, Adams KR, Sutton TE (1987). "Infectious diseases: pathophysiology and mechanisms of hyperbaric oxygen". Journal of Hyperbaric Medicine. 2 (3): 133–40. Archived from the original on 2009-02-thirteen. Retrieved 2008-05-16 .

- ^ Kawashima G, Tamura H, Nagayoshi I, Takao M, Yoshida K, Yamaguchi T (2004). "Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in orthopedic conditions". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine. 31 (1): 155–62. PMID 15233171. Archived from the original on 2009-02-xvi. Retrieved 2008-05-16 .

- ^ Baer M.D., William S. (ane July 1931). "The Handling of Chronic Osteomyelitis with the Maggot (Larva of the Blow Fly)". Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 13 (3): 438–75. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-12 .

- ^ McKeever, Duncan Clark (June 2008). "The Classic: Maggots in Treatment of Osteomyelitis: A Simple Inexpensive Method". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Enquiry. 466 (6): 1329–35. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0240-5. PMC2384033. PMID 18404291.

- ^ Aurégan, JC; Bégué, T (December 2015). "Bioactive drinking glass for long bone infection: a systematic review". Injury. 46 Suppl 8: S3–7. doi:x.1016/s0020-1383(15)30048-half dozen. PMID 26747915.

- ^ van Gestel, NA; Geurts, J; Hulsen, DJ; van Rietbergen, B; Hofmann, Due south; Arts, JJ (2015). "Clinical Applications of S53P4 Bioactive Glass in Bone Healing and Osteomyelitic Handling: A Literature Review". BioMed Inquiry International. 2015: 684826. doi:10.1155/2015/684826. PMC4609389. PMID 26504821.

- ^ Jeffrey, Janis (2009). "A 25-Year Feel with Hemicorporectomy for Terminal Pelvic Osteomyelitis" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Molnar, R. E., 2001, '"Theropod paleopathology: a literature survey": In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, Thousand., Indiana Academy Printing, pp. 337–63.

- ^ "First Evidence of Parasites in Dinosaur Basic Found". smithsonianmag . Retrieved 2020-11-24 .

External links [edit]

- 00298 at CHORUS

- Acosta, Mentum; et al. (2004). "Diagnosis and management of developed pyogenic osteomyelitis of the cervical spine" (PDF). Neurosurg Focus. 17 (half-dozen): E2. doi:10.3171/foc.2004.17.half-dozen.2. PMID 15636572.

belsteadquinginotted.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osteomyelitis

0 Response to "in the term osteomyelitis, what does the root refer to?"

Post a Comment